RUFF TRANSLATING RUFF RANTS

Brought to you by the Ruff Translating team!

|

Decompression is the process of relieving stress on your dog. Most of the time when you hear about decompression it is in regard to new rescue or puppy adoptions. There are so many articles and processes meant to guide you on how to reduce stress when you bring a new dog into your house. But what are we actually talking about when we talk about reducing the stress rate on dogs, what actually allows dogs to lower their stress level, and how do we use that in our training to ensure that when we are teaching skills we are also offering appropriate processing and relaxing?

Decompression is not “free time”. Decompression for dogs does not mean that you are letting the dog do whatever it wants- or doing a completely unstructured walk. That is a fundamental misunderstanding of how dogs think, and what it requires to settle anxiety or overstimulation in dogs. Recently, I have seen the resurfacing of a concept that I keep hoping will die, the idea of “dog led decompression” on walks or in other environments. The concept is that dogs need time to “lead” their handlers exploring scents etc. This isn’t a new idea, and may even be useful in certain contexts- but it’s also not decompression. Free time for dogs is fine, but it should always come with ample handler check-ins and boundaries. Why? Because it’s completely unsafe to give your dog free reign. We have a tendency to assume that decompressing for a dog is synonymous with what we may want as some humans- increased freedom. It is unwise to think that a lack of structure will somehow translate to the absolution of unwanted behaviors. At the end of the day, dogs are still animals, and frankly- shit happens. So what is "decompression" when used properly? Decompression is a training tool to increase a dog’s coping skills while also providing appropriate biological release of the pressure that comes with living in the human world. But much like if you were rising from a deep dive, and rose too quickly- you would suffer consequences, you are going to have a nervous or highly excited dog if you remove all structure. For example, if you are teaching a dog to have impulse control around prey animals or small dogs- you may have them hold place while presenting a distraction that mimics a prey animal (think like a squeaker toy) and offer rewards for holding position. At Ruff Translating, we would also correct any mistakes through guiding with a leash. The biggest reward is the release of earning the toy, that is what takes the pressure all the way off the dog. That, versus letting the dog just go ham on a toy with no boundaries- is the difference between teaching decompression, and overstimulating a dog. Controlled play is an excellent method of decompression. Again, we aren't talking just free for all ball chasing or tug (which also has it's place) but play as a release from structure. A huge component of relieving stress on your dog is channeling their natural energy and interest (drive) into a focused activity as a reward for impulse control. Here is a sample exercise you can do as part of a decompression protocol: While practicing going into a crate, and waiting for a release to exit, use your crate door to set a boundary if your dog tries to exit before you have given your release marker. Once your dog is holding position, give your release marker (most of our clients use "break") and guide your dog into a game of food chase, ball chase, or toy chase. Repeat this exercise until your dog has a light pant, then put them into a longer period of crate rest (2-3 hours of nap time). This can be done with dogs of all stages of crate training- because it is not solely about the crate. While of course you are adding value to the crate by playing a game- you are actually getting your dog into the right state of mind to use their crate properly. We crate train not only because we want to prevent damage to our homes or injuries/illness to our dogs, but because we want to teach them how to be still, and relax. Decompression activities can also include puzzles, snuffle mats, high value/long lasting chewing activities, conditioned relaxation massage, conditioned relaxation positions, and working for meals. When should you be thinking about decompression for your dog? Whenever your dog is exhibiting stress behaviors, or you are increasing the challenge of training substantially (either for rehabilitation purposes, or not), or there are big life changes. If a member of our community adopts a dog, we generally recommend focusing exclusively on decompression for 3-4 weeks before starting any time of focused training aside from leash manners and crate training. When we are teaching e-collar, we do a lot of decompression work as the process of learning this tool involves teaching complex markers as well as practicing object permanence. Decompression is useful when you move, add a member to your household, have a new baby... the list goes on. Many trainers and rescues will also talk about a "decompression protocol" which is just putting together exercises and boundaries meant to create a lower stress response and higher coping capability for your dog within a period of time. The key to making this a successful use of your time and energy is structure. Creating easy routines for your dog to anticipate, even if those routines vary in time-frame creates stability and predictability for your pup. This is important because the human world is scary and confusing. If you want your dog to be reliable, you need to be equally as predictable for them. Here is a sample of what a day may look like for a dog needing decompression: Morning: Potty Break, 1/2 breakfast fed in a slow feeder in crate Late Morning: Structured walk 25 minute walk (in heel, no marking), 1/2 breakfast fed for offering "look" outside Post Walk: Any remaining breakfast put into crate, 1-2 hour nap post walk Early Afternoon: Potty Break, Practice place holds for 45 minutes in increasing durations. Periodic place releases into play. Late Afternoon: Structured walk 25-30 minutes Early Evening: Wobble kong, puzzle, snuffle mat (any food game) solved inside of crate, Crate rest for 1-2 hours. Later Evening: Umbilical cord leash practice (for those unfamiliar, speak to a trainer about this) 30-40 minutes. Bedtime Routine: Last potty break, 15 minutes of conditioned relaxation massage, high value long lasting chew in the crate, goodnight pup! Additional Recommended Guidelines for Decompression

This may seem like a highly structured day, and it is- intentionally. One of the major reasons we see increasing or unresolved anxiety is from dogs who are unclear about the expectations before they are given freedom. Dogs tend to show a substantial increase in anxiety when there is a lack of structure. While my dogs do not need to follow this protocol all the time, we revert back into it when we travel to help establish some boundaries, or anytime we see the development of problem behavior. Training is a lifelong relationship, and there are always going to be periods where you need to refresh things to improve behavior, especially when you have a pack. This is a tool in the kit to bring your dog back down to a baseline expectation of behavior. It is the place we build off of to create dogs that are capable and comfortable with both boundaries and their doggie free time. A tip for creating a decompression protocol for your own dog is to consider your dog's natural biology, and work with it. For an easy example- we now know that sniffing lowers the stress rate in dogs by lessening their pulse rate. One could hypothesize (and some do) that this means we should meander and allow a dog to dodge every which way to sniff. This isn't exactly capitalizing fully on this amazing discovery to reach our training goals. I find deep stress relief in cooking a very elaborate meal- but I don't have time to make a 7 course dinner every night. Instead, I make time and space for cooking as a hobby. You can kind of create the same expectation for your dog, while still utilizing this valuable biological trick. You can use a snuffle mat or ball as a higher value reward during your decompression "place" practice. We find that if we include scent-work-like exercises with our dogs we can work with them for a longer period of time with better results. You can also pick a "sniff break" spot on your structured walks. The key is to make it a conversation between you and your pup- just because they like to sniff doesn't mean that is all our walk is for, or that you will never allow them to send that desperate pee-mail they have been drafting- just that the choices are not solely up to them. It is a partnership. If your dog is demonstrating any "back sliding" or resisting training sessions, or just generally overtired from a long ass year- integrate some decompression. Put yourselves on an accountable schedule, and stick to it for 2 weeks. Then slowly start reintroducing privileges. Your dog will thank you, and so will your trainers. Keep those pups cool, calm, collected, and engaged!

0 Comments

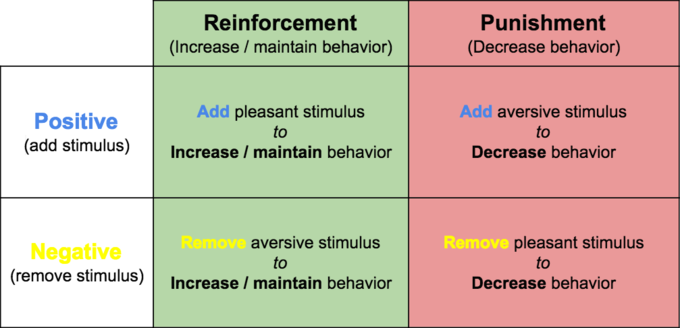

Ruff Translating is a balanced dog training company. But outside of the professional jargon, what does that mean? For us, it doesn’t just mean that we use prongs and e-collars. There are many dog trainers who identify as either “force free” or “pro-positive”, which is meant to indicate that they only use 2 quadrants of the 4 quadrants of learning, as described by operant learning theory. Here are the four quadrants, for those of you new to the world of animal behavior, and/or dog training. Skinner’s basic outline of the four quadrants of operant conditioning: Now, let’s dive down a bit more so that everyone is sure of what we are talking about in specifics. Positive Punishment This term indicates that some kind of aversive is applied with consistency until a behavior stops or is completed. For example- A typical e-collar training technique (not used at Ruff Translating) is to apply a low level stimulus during a command (recall typically) until the animal completes an action.Then, the pressure on the stimulus is released- which allows the animal to be rewarded with the absence of punishment for completing the action. Positive Reinforcement A positive reinforcement is the simplest concept to understand- we add a reward to the desired behavior, ie- a treat or a toy (even praise!) as a reward for completing the desired action. Negative Punishment This is when you remove something of high value in order to curb an unwanted behavior or draw out a desired behavior. For example, you may withhold a treat if a dog who knows an action doesn’t complete it. Withholding food is a negative punishment. Negative Reinforcement This is when you add something to a situation to get a different, more desired learned behavior. For example, leash pressure in response to a lunge at another dog. See also- a verbal correction. There is a widely known and highly public debate of which of the quadrants should be used in training dogs. It has become incredibly divisive and is something that Ruff Translating deals with everyday. Dog trainers who are highly in tune with only negative punishment (removal of food) and positive reinforcement (application of food) are portrayed as the “kinder, gentler” option for puppies, etc. Unfortunately, this narrow scope just isn’t always effective long term, once the food disappears, often so does the taught commands. Most K-9 trainers (police dogs, etc) are as well versed in the four quadrants, but tend to lean (this is a big generalization) towards negative reinforcement as well as positive punishment. Again, this is sweeping, and my attempt at trying to give context to where Ruff Translating finds our footing. Operant Conditioning is useful in understanding how to apply specific tools or actions based on creating an environment where we can better communicate with our dogs. But unlike a simple chart, there are no hard lines when it comes to understanding how these things play out in the course of training a dog. Things can get muddled very, very quickly. When I work with a dog, one of the first behavior assessments that I tend to make is the response to human voice as well as simple body language. I often work with dogs who are incredibly shut down. Many of these dogs are rescues who have been shipped, shuffled from place to place, and though likely not experiencing direct violence in previous homes, not exactly familiar with how to be successful in a human home environment. Usually in these assessments I will be met with a highly vocal, defensive animal, snapping, and lunging in my general direction. Often, I will be met with a shuddering, growling, eye dodging, scared little dog gremlin incapable of making friends. My initial response is always the same- pass me the leash. Generally, if given enough time and space to work, I can slowly use the leash to settle a dog. Maybe not to the point of being friendly, or engaged, but calm enough for me to have a conversation with the owners and start unpacking a training plan. If I was to offer 9.5 of 10 dogs food in this state, I would escalate their behavior. Or, they will come take the food as a reward, and then go back to their gremlin like state. Instead, I use gentle leash pressure, very firm, unyielding body language, slow breathing, and engagement to settle dogs. It’s a quick dance of moving them towards me, and away from me, and setting boundaries using simple dog body language roughly translated into human actions. I do not immediately throw them on a tool like a prong. I also do not feed them immediately. But where would this fall under the operant conditioning chart? More or less, everywhere. I apply short bursts of pressure to a leash to keep the dog close to me, but not able to over engage with me or the environment, which would be negative reinforcement. At the same time, I get the dog moving in multiple directions, trying to get them to follow my actions and engage, which could easily be positive punishment as I move the dogs around with constant short busts of leash pressure. I reinforce calmness, or enthusiasm with only verbal praise, depending on how well a dog responds to my actions, which would positive reinforcement. The entire action is generally done without the use of negative punishment, unless the clients who own the dog are a high value reward, which can be the case. Leaving out one aspect of this routine would never produce nearly the same amount of results. They have to work in conjunction. It’s not a clear cut category, actions overlap. The further that you dive into learning theory, the more muddled it becomes, and that's not a bad thing. More over to an extensive degree, focusing just on the types of methods used (some methods SHOULD be off limits- looking at you, Jeff Gellman) really limits the agency of the dog in question. All of the recent scientific data shows that dogs are actually deeply emotional, and incredibly keen at discerning human intent, health, and even mood. They plan actions, they have memories. When we reduce complicated relationship building to simply understanding an operant conditioning chart, we are underestimating our dogs to an incredible degree. One of the reasons we don’t use front clip harnesses for leash training is that I believe the restriction of movement without the benefit of clear communication, is a form of constant positive punishment. Constantly restricting the movement of your dog, by physically overpowering them and controlling their shoulder movements, is not a gentler method of training. Nor is it likely to produce an actual understanding of walking on a leash. But if we think of it solely in human terms- it LOOKS like positive reinforcement more than a prong collar does. It is only until we unpack the physical action, that we see the actual effects. Dog training has been in many ways, reduced to simply teaching a few key words, and feeding them as a reward for those positions- or forcing them into those positions for an undetermined amount of time. Sometimes a combination of those things. Why on earth would this be the place that we start? I understand why we may have started in this place, just wanting to communicate some basics. But this is not where Ruff Translating feels the focus of dog training should start, now that we have a more collective broader understanding of dog cognition and processing, nor is it actually historically how dogs and humans have collaborated. Instead, we need to be focusing on teaching our clients how to read dogs. Firstly, those teaching better be pretty good at reading dog body language. I’ve spent years, and countless hours, reading, studying and practicing understanding dog body language. We are going to get parts of it wrong- “dog” isn’t our first language but we should be making every attempt not to anthropomorphize but to instead really understand what’s going on. Dogs do not think or process the way we do. The structure of their brain defines evidence of this. But they are still highly emotional, and intelligent creatures. We often limit them by impressing our own feelings or assumptions on them. If a dog appears frightened, many people assume that fear is permanent (she’s always been skittish), rather than looking at ways that you can teach confidence rather than directly challenging a dog with their highest fear. We need to be teaching our clients how to form a different, stronger bond, with their dog first and foremost, so they can then fully understand how to train. Then we need to be teaching how to give your dog the skills to work through challenges, not just commands. Establishing a working bond takes time. When someone walks into Ruff Translating, they are often super nervous, (just like their dog), and scared that because they have sought help from a balanced trainer, they are going to be met with hard lines, and forceful punishment. Unfortunately, aside from the use of operant conditioning, K-9 training also reproduces many of the same issues in a training environment as exist in the institutions where it was created, because it is reproducing that inherently biased system for pet dogs. Thus, often it is not a conducive environment for queers, BIPOC, non-veterans with PTSD, other folks with disabilities, and other civilians to connect with their dogs outside of a command/response frame work. Those fears of violence or aggression are not realized when we apply balanced training, but we are capable of setting an appropriate boundary through the technical definition “punishment” if the case before us requires it. We bring out a wide variety of tools when there is a communication stutter- as an extension of allowing communication to move more freely. For example, we use prong collars because many dogs can’t feel pressure or understand what it means without those rounded, safely applied, mama-dog-mimicking little points of contact. Many of our handlers have substantial mobility issues, and can’t provide direction to their dogs without tools. We do not hold pressure on a prong to cause pain. We do not pop hard and mean. We don’t even sell prongs without a lesson on how to use them fairly, kindly, and to help your dog. It’s very similar to finding the right bit (the piece of a bridle that settles in a horse's mouth) for the right horse- tool selection can even change with each training situation you are in, to better affect what you are asking your dog to do. When I am trick training- it’s all lures and treats. When I am training for public access- and the stakes are very high for a service dog- I am not taking the food route, this requires a direct line of communication and a hair’s width of precision. I would like a bluetooth to my dog’s brain, which is leash pressure and body movement as well as engagement and verbal praise. The very first thing we do at Ruff Translating is teach foundational eye contact. We now know that there is a bonding hormonal exchange through direct eye contact. That hormone (oxytocin)acts as a familial love potion, literally. You can tell so much by the way a dog engages or doesn’t with eye contact. That combined with head position, tail position, tension, movement, and micro-expressions gives our trainers a place to start. And the place to start is to get your dog to hone in on your goals, your shared goals, and your boundaries as a handler. We can’t do anything until we build the relationship. Sometimes this happens quickly, other times it can take months. It is always worth doing, and there are a myriad of training exercises to help it along. But the point is that we aren’t starting from a place of punishment, correction, or even command response with food reward. We are starting from the place of relationship counseling. Just because your dog adores you, and is friendly, does not mean that they understand or trust your communication. Often friendly dogs are just a result of genetics, life experience and general temperament. A goofy, friendly, household pet is not necessarily trained in the slightest. Ask yourself some questions about your dog... Does your dog look to you over most distractions? Does your dog respond when you look in their direction without verbals? Can you get a tail wag with a smile their way? Can you communicate a “no” with a glance and body language and get results? Can they predict your actions based on how you move, and anticipate activities other than a walk or feeding time? Are they unsettled? Do they pace? Startle easily? Do they eat well? Do they have injuries? Is there pain that is limiting mobility and influencing behavior? This is where we focus our training. The connection and understanding, and when we do the rest comes along much further. There is no secret sauce in dog training, there is no magic. There is commitment, hard work, and a keen sense of observation. There is time and patience. There is persistence. You can take your dog to a group class and have it perform beautifully, including in dog sports, basic commands, competitions- you name it- but there is so much more out there. There is an ability to have the closeness you can see with a well tuned service dog handler and their dog, military dogs paired with a combat handler, and those experiencing homelessness with a pet. The connection is the actual magic. When you spend the time to learn how to communicate with your dog, and better read their communication, not only do problem behaviors improve but general stability, and frankly- tolerance for each other’s blind spots. The bond overrides the annoyances and allows you to work through them, or set a boundary that works for you both. This may sound humanizing, but it is not. It is very different to understand that a dog has desires and feelings then to believe those mimic ours. They are different, a dog’s sense of self is tied to a much different emotional understanding since they have evolved to engage with us as a method of survival. If you want to work with trainers who are deeply committed to building a bond with your dog, that’s where we fall. If you want to learn how to build that bond with your dog, we are here for you. If you want to be sure that your communication is clear, we are constantly working to clarify those lines the best way we can- through tools, through food, through verbal clarity- through engagement like eye contact. That’s what balanced training is to us. It is understanding that working with any animal is not just about getting results or about whose method’s work better- it is about taking the time to start from a place of comprehension, however shoddy, and then work towards making it clearer. That is training at Ruff Translating. We are not former soldiers or police officers. We are not hard line trainers. We do not use constant pressure e-collar stimulation and we are not rough handlers. But we are direct and we do think your dogs can do better, with your help. That help needs to be balanced and respectful of the very highly intelligent species we work with. I do not believe based on our scientific research of dog cognition that dogs are cookie eating machines. It is simplistic to believe that a dog can be given a high value food offer or removal and they will do anything you want. They will work for food and you can use it to reinforce- but if that is your only tool, you will be quickly limited and carrying a cookie bag for the rest of your life. That cookie bag may or may not be effective given the environmental distractions. There has to be more. And there is. We just have to take the time to learn it. “Are you force-free?” The caller on the end of the phone asks. “We are balanced.” I reply and everything is lost in translation. Somehow, years of connecting with dogs, years of study, courses, apprenticeships, field work are reduced to this simple interaction. I can feel the caller’s hackles go up. The internet struck again. I can feel visions of me blowing guns off to teach dogs not to be scared of loud sounds with no warning, prong collars with pointed ends, this is what’s summoned in reference to “balanced”... who wouldn’t be turned off? Instead we have visions of polo shirts with logos and treat bags, with dogs jumping all over each other and called “play” on the other end. Both extremes will harm dogs and why folks are confused. We are force-free, honestly. But we aren’t pressure free. We believe dogs are capable of experiencing an appropriate amount of pressure (not necessarily physical, it can be verbal encouragement) to work through their fears or reactivity and then be handsomely rewarded. But that’s not what the caller is asking. They are asking me to define a life’s work to a category, and the category they hear doesn’t even describe close to what we do here. I go on to explain more of how we work, and hope for the best. Based on our success, I know we are what folks are looking for. I am not sad to hang up the phone for lost business, fortunately, our results speak for themselves. But when I hang up the phone I am profoundly sad because in limiting our conversation to tools, we aren’t having the conversation we need to have. “Are you committed to changing the way my dog and I interact, and helping me learn how to do that safely, fairly, and with some fun?” Yes, yes we are. If you are too, we can help. Cities around the country are noticing an increase in fireworks, and Boston is no exception. We definitely have our share of booms starting at about four o'clock in the afternoon and going long into the night. My personal dogs have always been pretty chill about fireworks; they don't love them, but it hasn't ever been a behavioral trigger, thanks to a combination of good temperament and a lot of desensitization training. Rio, my service dog, has attended a number of fireworks displays at Disney World, so she is especially relaxed about it all. Recently, however, Swanson started showing some fearful behaviors, likely because the sheer volume and consistency of noise has increased. We have had a lot of Ruff Translating community member questions about how to manage firework anxiety, and with the holiday weekend approaching, we wanted to share our best practices for coping with the noise. Swanson is now doing great with the increased volume of fireworks in a matter of less than a week. Remember, like in all things dog training, there is no silver bullet. There are multiple strategies that combine training and management. It takes time to find the magical combination that allows your dog the right coping skills to conquer anxiety and fear. We are here to help you get started with some of our best practices. If you dog has a high level of anxiety already or isn't fully crate trained, we strongly recommend joining us for a private lesson so we can better assist. 1) Get ready for the noise! Extra exercise or a high impact training activity, especially directly before fireworks start -- or even during if you can still get focus -- will help your dog start from a more relaxed place. Lack of impulse control and anxiety will be elevated if your dog's mental and physical stimulation needs have not been met for the day. 2) Restrict wandering! Yes, seriously! Just like many anxious people can get themselves worked up with repetitive behaviors like pacing, dogs who have trouble settling will often resort to "flight" behaviors. This will only increase their anxiety. Instead, provide a limited amount of space for them to hang out in. We recommend sending a pup to their "place," or if they are extra distressed, going ahead and helping them settle down in their crate. It's OK to move your crate or place set up to an area where you are also present. Sometimes that can help, too! At the very least, shut extra doors and restrict movement to a centralized room. With Swanson, we worked really hard on just sending him to "place" and reinforcing that he couldn't run through the house and hide. This allowed him to both be "in-command," which gives him clear expectations, and safe, as "place" is an extension of our crate training. If he were younger or less stable, I may opt for the crate. 3) Drown out the noise! White noise, the television, an air conditioner -- literally anything that reduces the amount of sound that's entering your pup's space. They are still going to hear the noise, but you can cut it down a bit. We like the Cooking Channel or young kid's cartoons for our pup's television background options because the voices are usually calm/friendly. A lot of our dog friends also enjoy talk radio. 4) High value CHEW activities! Chewing reduces stress and releases soothing hormones that help dogs relax. The act of chewing for a dog is similar to us getting a nice shoulder massage. Many, many dogs are too anxious to work on their typical treats, so pull out the extra stinky, extra delicious options! Bully sticks, naturally dried ears, trotters, etc. -- something that is nearly irresistible! 5) CBD! We love pre-measured chews and high quality CBD treats. The trick to using CBD effectively is to find a brand that is growing strains that are beneficial specifically to dogs with strict testing for dosage and purity. Our two favorite brands are Suzie's CBD and Treatibles. In our experience it is most effective to use pre-measured treats instead of oils. We love a Treatibles cookie dipped in Suzie's CBD peanut butter for those extra hard days. Dosage guides are available on each company's website, but you can always reach out to RT if you have questions on your specific pup's needs. 6) Get into a routine. Make the firework prep routine normal, especially on the weekends, even if you don't think you will need it that evening. Dogs LOVE predictability and schedule. If you practice the firework bedtime routine, it becomes a lot more familiar, which also helps reduce anxious reactions. 7) Desensitization exercises! Sound desensitization should really be done with the help of a professional trainer. We have had excellent results in combining scent exercises with increasing levels of firework sounds. Scent work, sniffing, and the like lowers dogs' blood pressure and heart rate, so combining that with unfamiliar, scary noises can be really therapeutic. These exercises require a keen understanding of your dog's stress threshold and how to SLOWLY increase the challenge to keep them successful. To get started on your own, play a low level YouTube video of fireworks on your phone -- be sure that the volume is set fairly low -- and practice "look" with a high value reward. Once you have eye contact, release your pup into a scent activity like a puzzle or a snuffle mat. For more involved exercises, please reach out to us for help! 8) Get your leash! Avoid baby talk and instead get your communication line open. Dogs speak really limited human language, but they are body language and pitch geniuses. If you melt when they melt and start using really soft, concerned language, that can accidentally reinforce their fear. It is totally reasonable to show kindness to your scared pup. But, remember, human kindness is not the same as dog kindness. If your dog is struggling, put them on a leash and do a few leash work exercises (ie. heel positions; rounds of soothing pressure using a K9 Lifeline transitional leash; practicing "center," "tuck," "right," "left"). Even just being on a leash and walking slowly around a room and forming tight circles can reconnect and refocus a dog. Try to remember that connection through the leash can help a dog, but coddling can reinforce their fear. Get into your dog's needs, and show them that you know they are scared but they can totally handle it and work through it. We recommend keeping a few slip leads around as your house leash in times where your dog needs a little extra reinforcement. 9) Adaptil diffusers! Adaptil is a synthetic pheromone diffuser that mimics the pheromones released by mother dogs nursing their pups. It takes about three days for the effect of an Adaptil plug in to be noticeable, so order or pick one up and get it plugged in near to where you want your dog to settle for fireworks. We recommend leaving them plugged in by your crate full time, but they also have GREAT travel products. Adaptil spray can be applied to bedding or bandanas for a more instantaneous effect. It is far from a panacea, but with the other tools we mentioned, it can really boost the progress your dog makes. Truly, with all scary sounds, the most important things you can do for your dog is provide a safe place to be, provide structure, and reinforce their coping skills using training exercises. If you can work on a solid plan for your pup to work through their firework or thunderstorm anxiety, it often will also have behavioral benefits to other scary triggers! It is worth the time and effort to help your dog go through fireworks successfully so that they can be more confident and stable as you meet new challenges together. You can check out one of our buddies, Ms. Bailey Bae, working on her firework anxiety at Muttessori Academy last week! We are always happy to help you tackle these real world training goals through our day programming! Black Lives Matter: How white people's choices in dog ownership perpetuate racism and violence6/1/2020  FB memory from 2019 FB memory from 2019 I have been trying to figure what to say as white dog business owner about Amy Cooper. Amy Cooper is the white woman who called the cops on a black man who asked her to leash her dog, in an attempt to cause him serious harm. She was not at any point in physical danger, and she even actively physically threatens the space of her victim Christian Cooper who asks her to stay back. PS- We are in the middle of a pandemic and her mask is draped across her chin, so as better to use her "call the cops" panic voice. I keep thinking, over and over, is that it is deeply ingrained white privilege that assumes you don’t need to have control over your dog, or follow rules regarding dog management (ie: leash laws, poop scooping). Firstly, I will be honest and say I didn’t notice Amy Cooper’s former dog struggling at first in the now infamous video. The pitch of her feigned terror, the laid out plan of threats, the knowing look in her eye- it was all too familiar and I was focused on her lies and the danger she posed. If you haven’t seen the video, take the time to watch it. Many white animal lovers noticed the dog first, which is undeniably racist. Yea, she manhandled that dog during the conflict. She manhandled that dog with a lack of compassion that paled in comparison with her maliciousness in threatening Christian Cooper, a queer comic trailblazer, Harvard grad, and innocent bystander to her law disregard. The dog was in short term, minor distress. Christian was in peril. That is the reality of policing in this country. And that is what we need to be focusing on. The RT team is regularly engaged in these typical interactions. A poorly trained, off leash dog comes bounding up to our structured pack, with their white owner waving their hands, sometimes attempting a failed recall, sometimes yelling about the supposed friendliness. Often times, these instances escalate quickly, and several of my team are vulnerable to police violence, but none in the very specific way that a black man is, as we currently do not have any black men on our staff. During a recent family photo shoot, I asked a white man to leash his dog in a leash-only section of a local park. I am direct, firm and unyielding. I am also incredibly visibly queer, and so is my spouse. The enraged white man began threatening us, causing a scene. It was ugly. Cara (who was also having family pics taken) had to step in with her dog Jonas and offer to remove his muzzle if he continued harassing us. The white man had his dog in a non-off leash section, had little verbal control, the dog wasn’t wearing the required license tag to access the off-leash space (known as a green dog tag). Rio, sensing my panic, was in a full shield bark in a blocking position. I asked the man to leash the dog because we had our full pack on leash, and were taking a few pictures when the off-leash dog entered into the shot. The mere suggestion of a leash turned to aggression in almost no time flat. If the cops had been called, I would have run. Trans people are not safe in police custody. But the man didn’t threaten that, which one can assume was also because we are white, and eventually wandered away to ruin to someone else’s day. I know that had we been Black, it would have been exponentially worse. This guy wasn’t going to tolerate two white queer folk telling him to leash up- with a pack of 3 (then 4) defensive dogs, and a photographer and a witness. If we had been anything other than white, we could be dead. By the police. For asking someone to follow basic regulations. Today, June 1st, a memory popped up on my Facebook, and I hesitate to share it because I don’t want to take away from the the fact that we need to focus on justice for Black folx, individually and systemically. But I want to drive home the incredible, presumptuous privilege, that comes within white people and dog culture. Last year I was assaulted 4 notable times (and countless stupid verbal interactions) as a visibly queer person with a service dog. The first time, I was grocery shopping. I had my back turned to Rio, who was standing in a tight position behind me, facing the cooler I was reaching into. A kid, between the age of 6-8 waltzed up to her and gripped the fur on her back. I startled as Rio changed position, and turned around. The child knew she had done wrong. I calmly said “Stop touching her. It is incredibly rude to touch a service dog. Go away and find your parents.” The child began to cry. I do not feel bad, I wasn’t overly cruel, and this kid was screwing with the settings on my medical device while I tried to get through an errand. It is not my job as a person with a disability to make other people’s kids comfortable with my adult with a disability boundaries. When the kid returned to her dad crying- he came at me. Up to this point, nose buried in his phone, he was not paying any attention to his kid, who had wandered 3 aisles over to harass me. He ran up to me screaming, and threw a punch, which I avoided mostly because he couldn’t get too close to me because Rio was in a front shield (creating space). He threatened the dog, he threatened me. Customers all around us watched silently. He then tracked me through the store until I went and got a manager, which I could do because I was white- who made him stop but didn’t ask them to leave- because the man's comfort was still more important my safety as a transperson with a disability. White privilege is in EVERY action, EVERY system, every engagement. I have it, even as a trans person with a disability, I would be impacted differently, and more severely if I was also a person of color. It is a place of privilege to believe you are above leash laws. It is a place of privilege to believe that your dog deserves better treatment then black people, subconsciously or actively. It is work to change the inherent racism that permeates white people's actions. We must do it. My dogs have their own bedroom and are the most spoiled creatures that have ever lived. But they do not deserve to run off leash more than anyone else deserves to be comfortable in their presence. To go one step further, I believe that it comes from a place of privilege to not properly train or manage your dog. I am not talking about the people who can’t afford professional help, and are googling the best they can while wrestling their pup on a leash. I am talking about the Karens who believe that if I am allowed accommodation for my highly trained service dog in public, they should be able to shove their doodle into a vest because they like having their dog around. I am talking about the Amy Coopers who believe they don’t have to leash their dogs, and when asked, threaten murder. That’s what calling the cops on black folk is in this situation- threatening murder. Dogs have a long and complicated history of being involved in racial violence, and comment from the President this week reinforces this. To quote Donald Trump, he threatened with “The most vicious dogs”. Do you know how white people, especially law enforcement, have weaponized dogs specifically to terrorize black communities? They have, and there is a long historical record of it. You can do some further reading, here. White people, white dog owners- we have a lot to do. We have a lot to be accountable for, we have a lot to work incredibly hard to dismantle and make better. But don’t leave your dog ownership out of it. Do not weaponize your dog by refusing to leash, by poorly training recall, by not using an e-collar to reinforce and correct misbehavior in high distraction environments like public parks, faking service dogs, by not using long lines. Your dog does not have the automatic right to access to off leash exercise over the right of black people to live. You do not have the right to assume that your dog is “good enough” when it could terrorize another human being- simply by approaching them. As white dog professionals, we have the obligation to call in our clients, ensure that they understand that anything less than 100% recall means we stay on leash unless we are in a designated, fenced, dog area. As white dog professionals we have the obligation to follow leash laws and encourage others to do the same. As white dog professionals we have the obligation to recognize the role of dogs in systemic violence, and work to create avenues that allow safety, emotionally and physically, for those afraid of dogs. As white dog professionals we have the obligation to provide a welcoming, safe, informed environment for BIPOC seeking services and support for their own dogs. We have the obligation of calling in white dog owners who believe their dog is "inherently racist". Ruff Translating’s official company stance is that we are with Black Lives Matter. We stand against police violence. And we stand against the Amy Coopers of the world who are irresponsible dog owners, but more importantly- are so entrenched in dog owner privilege they commit racist acts endangering the lives of those more vulnerable. Don’t call the cops. Leash your fucking dog. And remember that training is the only way to access public spaces, and that your poorly trained dog is a threat to the safety of both people and other dogs. White dog culture is not just memes, it’s not just dogs in sweaters, it is also deeply entrenched entitlement. That entitlement is downright dangerous, for people and dogs. And we must change. Written by Sam Martinez

Apprentice Trainer “Adopt, don’t shop.” It’s something all of us likely have heard from proponents of animal rescues at one point or another. And while we here at Ruff Translating certainly are huge supporters of rescues, we’re not big fans of that popular phrase. For starters, adopting a dog is a shopping process itself, and potential owners should be prepared for that. While it’s entirely possible that someone could go to one rescue and find the perfect dog for their family that day, that’s not always -- and most likely won’t be -- the case. Instead, owners should start by researching local rescues and compiling a list of the ones they want to check out. You also should get an idea of what kind of dog you want, even if you’re not looking for a specific breed. The types of characteristics you can consider are things like size, activity level, coat type, and health. There’s a lot of research to do before getting a dog, even if you’re willing to be flexible once you actually go to a rescue! The more damaging part of the phrase, though, is that it suggests buying a dog from a breeder is a bad thing, when that couldn’t be further from the truth. Service dogs are the first thing that comes to mind when we talk about the necessity of reputable, responsible breeding. Choosing a rescue dog already is labor-intensive for someone looking for a pet, but it’s even more so if you’re looking for a service dog. Service dogs must be stable, smart, and free of health issues, and finding all of that in a rescue dog can feel like a one-in-a-million chance. Many service dog handlers also prefer to raise and train them from a young age, and it’s very common for puppies to come to shelters from backyard breeders, puppy mills, or because they were taken from their dam too early, all of which are highly unlikely to make a good service dog candidate. Simply put, it’s wildly unfair to expect people with disabilities to have to put the extra time, travel, and money it will take to evaluate a rescue dog into purchasing what already is an expensive and time-consuming medical device. You can learn more about what goes into making a service dog a service dog from our owner Ejay Eisen here. But there should be no shame in using a breeder to get a companion dog, either. The mere existence of rescues proves that not every person should be a dog owner. But we also have to reckon with the fact that not everyone should be a rescue dog owner. Rescue dogs can be extremely difficult trains, and just because a potential owner doesn’t have the experience to put in that kind of work doesn’t mean they won’t be able to train any dog. Dogs in shelters can be a unique challenge! Rescues also aren’t always the best at placing dogs in the right homes, by no fault of their own. They rely heavily on volunteers and donations, which means there are many people involved who aren’t experienced in knowing the kinds of behaviors and body language that can turn difficult or even dangerous. They are unbelievably well meaning people who don’t want to see dogs living their lives without a place of their own, but when your bottom line is getting them adopted, the lines between wanting to see a dog in a home and wanting to see a dog in the right home can get blurred. Plus, when the ultimate goal is to get all dogs out of shelters, how would people continue to own temperament- and health-tested dogs without responsible breeders? Ultimately, what we’d like to see is people fighting to help rescues employ dog trainers and behaviorists who would be able to make rescue dogs more accessible to owners, especially first-time owners. But for now, we need to make sure rescue dogs don’t get bounced around to people who aren’t quite ready for that type of responsibility yet. A stable purebred dog can be a gateway into getting a new owner excited about training and give them the experience to make a rescue dog their next choice. Good breeders also make their clients sign documents that include language stating that if the dog needs to be rehomed for any reason, it should be returned to the breeder, which will prevent more dogs from winding up in rescues and shelters in the first place. When it all comes down to it, we all want to see a world full of healthy, happy dogs. And if breeders play a vital role in making that happen, then we shouldn’t be shaming any potential dog owners for using them. Written by Cara Wehmhoefer

Lead Trainer In my past year of teaching private lessons, the subject I most often run into first is decompression. We trainers see it too often: A dog gets adopted, gets thrown into a handful of overstimulating situations too soon, then becomes fearful and reactive. The same goes for a dog and family that has recently relocated. Many of these behavioral issues they face could have been managed or prevented with proper decompression. We often hear from clients, friends, and family who are moving soon or are getting a new rescue, and the most frequently asked question we receive is, “How do I get them settled into their new space?” There are a number of answers, but what we always say is make sure they have proper decompression. The word is very simple: to release from pressure. In the context of our dogs, it is to release them from any and all excess stress and stimuli during a time that is challenging and stressful. We use a decompression protocol mainly in two instances: when a family is relocating to a new house or when a family acquires a new dog. Many of our dogs have struggled with behavioral challenges in the past that we are still working through and continuing to manage. Many of us also will be working through them for the rest of their lives. We do this, with the help of our trainers, by creating an established routine with a training and exercise regimen that best fits our dog. When life happens, and we move, it is important that we stick to these very same routines, but add in another layer that we call a decompression protocol. What would this look like? It can vary depending on the dog, but the principle is the same. A decompression routine is mainly lots of time in a confined space, with short bursts of structured walks, quick training and play sessions, and supervised yard time. If your dog is not crate or space trained, make sure their downtime is in the quietest part of the house. The dog does not get very much freedom at all during this time to minimize their need to make more decisions during a heightened period of stress. This is the main purpose of decompression: to release the dog from pressure during a stressful time. Let’s talk about moving houses. It is easy to imagine that dogs can sense a routine change. If they see suitcases, they know something is about to change. That may be a known pattern for some. However, it is very important to note that there is no way for them to know what actually is coming next. The furniture starts to disappear, boxes start to pile up, and their humans are extra stressed all the time. That is very anxiety-inducing in a dog! This is something many people miss amid the craziness of their own routine changes. Everything starts to change for your dog before the biggest change, putting them in an increased state of anxiety already. In order to manage this, we have to keep their routine as consistent as possible leading up to the move, adding in some decompression time as we go. Supplement extra crate time, especially during the busier moments, like movers and family members coming and going. Keep things quiet on the training front with low-stimulation walks and avoid any new or harder concepts until after everyone has settled into the new place. Another option to consider is boarding your dog with a trusted friend or dog sitter who can keep your dog in a quiet, steady routine during the busiest parts of your move. I made this choice with my personal dog, Jonas. I sent him to my trusted friend at South Shore Dog Squad in Abington, Mass., where he got daily structured pack walks, downtime in a crate, and lots of yard play. While it mainly kept Jonas from absorbing the chaos and anxiety that is moving, it also took the weight of maintaining his routine completely off my shoulders! All I had to worry about was packing and getting myself to the new spot in one piece. I got settled in, then I brought him into our new established space. His crate already was set up and ready, and I had plenty of stuffed Kongs ready to go for his crate time. After your move is complete, make sure your dog has their own quiet space where their crate will be. Set up a noise machine or radio, a crate cover (not all dogs enjoy this), an Adaptil plug-in, or anything else you feel would enhance the space. As soon as your dog arrives, begin your decompression phase. Here is an example of what decompression would look like in a single day. We normally suggest implementing this for about two weeks. After that two-week mark, you can slowly start to add in more freedom and privileges over time. Please understand that these are approximations and we acknowledge that every dog is different and needs will vary! 7:30 a.m.: Wake up and potty/20-minute morning walk 8 a.m.: Breakfast in a Kong or Toppl in crate 12 p.m.: Midday walk/training session/yard play 12:30 p.m.: Back in crate with snack 5 p.m.: Evening walk/training session/yard play 5:30 p.m.: Dinner in Kong or Toppl in crate 7 p.m.: Supervised free/cuddle time, on leash (This is a great time to work on conditioned relaxation!) 8:30 p.m.: Nighttime potty 9 p.m.: Bedtime If your dog is not crate or space trained, dedicating conditioning exercises to your training time will help them to learn more settling and coping skills! This same routine can be applied to a newly adopted dog or puppy. These dogs too often come from backgrounds of very little stability from being bounced around or living in a shelter environment. The best gift you can provide for them is that stability they never had. Think of your decompression protocol as a clean slate for not only your dog but for you as a human. It is a chance for you to leave behind old patterns that didn’t serve you and start fresh. You never know, you may have needed it more than your own dog! Written by Ejay Eisen

Founder/Director I'm sitting on the floor, staring dead into the eyes of a service dog candidate. I take four deep breaths very quickly and outstretch my hand. The dog stares at me, and after a moment of comprehension, he presses his nose softly and repeatedly into my palm. I say, "Yes!" but quickly start breathing in the same rapid succession, this time covering my face. First, the SDIT (service dog in training) taps my hand again. I swallow hard, working to not accidentally trigger my personal service dog, who is curiously looking on from a crate. She is concerned but wise enough at this point to know I'm not actually in panic or medical distress. She has watched me teach behavior interruption countless times. She knows that the first step is a touch, "Hey, you, you ok?" and the second step is a demand, "Hey! You need help, focus on me, the dog!" I continue my out-of-breath actions until the SDIT in front of me begins to bark and paw at me. "Yes!" I call to him and hand him a food reward and a thorough pet. I then move into laying still on my side and ask the dog to lie down. He complies, but not directly next to me where I patted the floor. "Uh-uh," I say, tapping closer to my body. The SDIT continues to stare at me. He then gets up, scoots over closer to me and lies down. His fluffy ears land lightly on my hand, and I give him a pat. "Good boy!" I say, rolling over into a position where I would be draped over top of him if I was applying any of my body weight, but we are just practicing, so I am just hovering in that position. I give the verbal cue "stand," and the SDIT pops up into a sit position. "Uh-uh," I say again while giving the hand signal for stand position, all while crouching, trying to both mimic the position of a handler in need without adding my body weight. The pup rises into the stand position, and I reward with kibble from my training vest. I slowly perch my body into a squat and lay my hands across the dogs shoulders, pushing lightly but firmly. I cautiously watch him adjust his position, and his muscles brace. "Good boy!" I whisper, then I remove the pressure and bring my own body into a standing position while still leaving my hands on the dogs shoulders. The SDIT being described will do this exact round of drills with me and my training team hundreds of times, and then even more with his handler as part of their team pairing. Team pairing involves teaching the handler with a disability every aspect of working and care of their service dog. Slowly, we will begin adding appropriate weight and pressure to the mobility tasks of helping a handler off the ground as he builds skill and muscle. When this dog has graduated from our program, he will have no less (and likely more) than eight separate tasks for his handler, who has a different scope of needs for her dog's assistance. She needs signals for certain medical onsets, relief for symptoms using deep pressure therapy, and mobility/stability support for bouts of severe dizziness. She needs a dog who can fetch her medication, her phone, her keys, water, pick up his own leash, turn light switches on and off, travel on construction sites for her job and go to concerts (both with appropriate protection), fly on airplanes for travel, be silent in classrooms and her office, and keep her safe, always. We have been training her personal service dog for almost a year, and he is nearing the completion of his training for graduation. But the work of pairing his tasks with his full time handler and ensuring they are a well oiled team will be a lifetime of commitment. The requirements for an ADA service dog seem fairly straight forward until you get into the work of training a comprehensive service dog for a person with a disability. A service dog is a dog that is comprehensively trained to perform a minimum of three tasks directly related to a defined disability (yes, there is a qualifying list). Most of the service dogs that I am lucky enough to know, and all of the ones that Ruff Translating trains, have a minimum of five tasks. A thorough training program will generally run for 12 to 18 months from basic commands up through task training, but it can be more or less depending on the needs of the person with a disability, as well as the dog's temperament, learning style, the skill of trainer, etc. It is perfectly legal for an individual to train their own service dog, but we do not recommend going it alone. Mostly, this is the case because we want anyone with a disability to have the BEST service dog they can, and we spend our lives studying the science of dog training. We are more than happy to partner with clients who want to do some of their own training and prefer to develop a custom training plan individually for those who want more engagement in their service dog work. One of the most common things that I hear traveling about the world with a service dog at my side is, "Ugh, I wish I could take my dog everywhere. You are so lucky!" Any time I hear this, my entire body goes rigid, and I swallow the acid retort on the edge of my tongue (admittedly, sometimes I don't). The commitment of a service dog is substantial. Not only because of the time, money, and emotional labor of training, but we have to have the appropriate gear, and I plan my life around making sure both of our needs are always met. If she is sick, I stay home. If she is tired, I stay home. I can not function fully in public without my service dog. I tried unsuccessfully for years to do the tasks she does for me. I am lucky that I am a dog trainer and that I managed to rehabilitate a purebred Australian shepherd that was surrendered over enthusiastic behavior that resembled a shark on a pogo stick when we first met. To clarify, I own and trained a rescue dog to be my full time medical alert and response service dog. So, should this be the primary model of service dog training? I don't think so. I am in the unique position as a dog trainer with a disability and a working service dog. Even more so, one of our primary specialties at Ruff Translating is working with recently adopted rescue dogs, in particular, highly anxious and sometimes aggressive rescue dogs. This has given me a lot of time to both research and reflect on the common adage of "adopt, don't shop". There are a lot reasons that this is a false narrative, and there is a lot of reading you can do about the profitability of rescue culture, the way in which it sometimes can create further income streams for puppy mills, and the lack of behavioral histories that are gathered. What I will say is that when folks come to our doorstep, they are often at their wits' end in a very short amount of time. I love rescue dogs -- I love all dogs -- but I do not support rescue culture that does not inherently work with appropriate behavioral screening processes, have a lifetime return policy, or rescues that do not support and understand behavioral euthanasia. I am not willing to debate these points. I have sat on the floor with too many dog parents, sobbing with them, as we have had to say goodbye to a rescue because they came to them too injured -- either behaviorally or physically. Endless resources and top of the line training or medical care can not rehabilitate every dog. We do not know enough about how dog brains operate to be able to solve every problem, and sometimes the management of a highly aggressive dog leads to a quality of life that is not acceptable for either the dog or the person. Recently, the lead trainer at Ruff Translating found herself in an online debate with a likely well meaning, but highly uniformed individual arguing the case for all service dogs to come from rescues. We are here as your resource to set the record straight. This is a terrible idea. Service dog training is a substantial investment, costing their handlers tens of thousands of dollars over the course of the training. Even when you can find that cost covered by non-profits who specialize in assisting those with disabilities, the cost to the training organization or the non-profit remains the same. The "profit" margin on training these dogs is nearly non-existent, but their value is well worth the work. The intensity, the exacting nature of the training needed, and the skill set of the trainer are simultaneously in short supply and high demand. Dog behavior is not simply a result of training or of genetics but a combination of all of that and then some. Lifestyle, early formative experiences, genetics, training tactics, exercise, diet -- the list of factors that influence behavior goes on and on. When I am looking for a potential next candidate, I need as much information as possible because I am working to train a working medical device and a stable, eager to work, happy critter who is strongly bonded to their handler. Dog behavior is even influenced by the way in which they are weaned as puppies. I have a moral obligation as a service dog trainer to ensure the highest success rate possible, both from a fiscal perspective and as an ally to those with disabilities eligible for a service dog. Sometimes this means I can screen a rescue puppy (in this scenario, a puppy is under 10 months of age) and see all of the temperament requirements, only to see a developmental or physical issue pop up six months into training, and the dog is not longer a candidate for service dog work. Finding a rescue dog that even meets the initial criteria is incredibly challenging, especially when you can't screen the parents for potential temperament or health issues. It's a best guess with very little assurance. Even an educated guess is wrong a significant portion of the time, at the cost of both the dog and the person who they were intended to help. People with disabilities are not obligated to perform a social good (assuming that rescuing is a social good, which there are many conversations to have) in order to obtain a service dog. In fact, we should be working to make more service dogs easily available to people with disabilities. We do not do this by throwing dogs that are not temperamentally prepared to work in this way into SDIT programs. We do this by making sure that folks with disabilities have living wages and social programs that support their access to appropriate care. We do this by building organizations that pay professional trainers to assist and train service dogs at reduced or no cost to clients. We also do this by realizing that responsible breeders are integral to service dog programs. Responsible breeders have genetic testing, are familiar with behavior screening, and select lines for temperament. The responsible breeders we work with also have a lifetime re-homing policy where they accept all of their dogs back if needed. There are so many fewer surprises with a well bred dog, specifically in regards to service dog training. I can build a relationship with a breeder I trust and work with them to find the right dog for a potential handler with everything from the dog's weight -- it's crucial for mobility tasks because you must have a dog that is appropriately sized for stability support -- to coat length, to a predisposition to fetching or other tasks we can mold into disability support. Responsible breeders screen homes thoroughly. They also screen dog trainers who run service dog programs thoroughly. I have a relationship with one breeder who gives us a puppy ahead of training, and we do not pay the purchase price until the dog has passed all of its training and found a handler. This allows us to help a client fundraise in a myriad of ways for their service dog as a partnership. As a newer program, this is an invaluable connection. I may be able to build a similar relationship with a rescue, but without all of the knowledge of what that dog has experienced. Training rescues with wonderful temperaments, as well as behavioral issues, is one of my greatest joys and one of the most worthwhile endeavors of my profession. But that does not mean that a rescue dog is for every owner. It is inherently ableist to assume that a disabled person has to adopt a dog with no knowledge of their history or genetics and force it to become a working service dog. Or that a person with a disability has both the capacity for rehabilitation and for the use of a working service dog. Service dogs are not pets. They are assistants, companions, and colleagues. They are also not indentured servants of any capacity. Dogs have co-evolved with us literally for thousands of years and survived because of our mutually shared benefit of collaboration. There is nothing unethical, shameful, or wrong about obtaining a well bred puppy from a responsible breeder for a service dog program. In fact, it is much more likely to ensure success for both the dog's lifetime of partnership and the handler's. The most important thing we can do as dog advocates and professionals is place dogs in the RIGHT home, not in just ANY home. And no, I will not dignify "should dogs be service dogs at all" with an answer. If anyone would like to tell my service dog, Rio, she is forced into retirement, they are welcome to try. She's better at handling that argument then I ever will be.  Rocket demonstrating the helpful use of a yoga mat during trick training. Rocket demonstrating the helpful use of a yoga mat during trick training. In a time of preparation, action, and holding pattern–a lot of folks are finding that their daily routines have been substantially altered. Losing jobs, working from home, kids not in school, activities changing- etc. So let's discuss how we can help our dogs adjust to the stress, and help ourselves keep some structure at the same time. We know the world is a really challenging place right now and hopefully every lit bit of what we CAN do will help. Don't get lax with the rules! Just because your office is a couch, doesn't mean that Fido should spend the whole day up in your grill helping send those emails. For those not able to work from home, but still confined due to closures- the same applies. It's 100% fine to do some bonus snuggling when you need it, but remember to still be sure to keep some strong expectations in place so that your training doesn't backslide while we navigate this new territory. It's okay to crate when you are home! In fact, we'd recommend a few hours of crate decompression time. We all are showing more signs of stress, and giving your dog an "out", particularly with a high value treat is a good work exercise for them, and will help them manage their stress. Let them worry about just "dog time" for a period of time each day, it's good for them. This is especially important for dogs who share homes with kids that are home too. It's a lot of activity if you are used to sleeping all day! Ensuring that your dog gets adequate rest and time to relax will help prevent stress or new unwanted behaviors. Still walk your dog. Go outside! Don't stop and hug the neighborhood, but get that dog on a leash and go for a neighborhood walk. Practice an automatic heel, work on eye contact- have them do "paws up" on surfaces- it's a killer way to spend a lunch break when you are tired of skyping with your boss or just burn off a little of your own anxiety. We know, it may sound a little trite, and it's not going to fix the stress many of us are coping with, especially those in the service or event industry. But let's all agree to get moving and that practicing eye-contact with your dog will release some oxytocin, which is better than nothing in times like these. Remember your indoor fitness and training activities! Balance pods, sound sensitization, treadmill running, puppy burpees and sit ups are just a few ways to keep your dog fit and busy in short bursts. We can commit to doing 15-20 minutes a day of focused exercises on most days. It will help both burn that excess excitement and energy, but there are other benefits. The engagement will help them also understand when you set a firmer boundary because you have to focus your attention elsewhere and they are staring at you with their ball in their mouth. I mean, speaking from experience as an owner of a border collie-- 90% of my time is being stared at anyway. Keep mealtimes and potty breaks consistent! One of the major struggles we see with work from home humans originate because the routine is flexible- dog care can accidentally become inconsistent. Try to stick with the usual mealtime routines (don't forget it's great practice to at least train through 2-3 meals per week), and keep potty breaks in line with what you usually do- even if Covid19 has you doing them yourself instead of hiring a service. This will help your dog feel physically more regulated, and prevent any new unwanted potty behaviors during this time. Work that "place" duration!! Send your pup to place, and make them practice just being present and still. Set up your "place" with either your place board, bed, etc in proximity to where you are at home, and use intermittent food rewards to reinforce holding position. You can do the same with the command "tuck"! This is a nice passive way to work your dog while you are going about your day. In times of uncertainty, it is so hard to feel like we have little control, because we have literally, little control. I'm glad that I have dogs to help me practice social distancing, and it's not a bad time to work on their trick titles, either! It is not easy to learn to read another species' body language. Heck, it's not even easy to learn another person's body language or facial expression. How many times have you thought that a new person you've met was expressing an emotion that they weren't aware what they were conveying. I mean, we've all heard of Resting Bitch Face. Still, though it's not perfect, we use each others body language and facial expression to convey and receive all kinds of important information. There are a lot of great resources online to get you started on reading dog body language, but truly spending time with you pup will help you notice patterns best.

So many people misread their dog's reactivity as aggression. Just because a dog is making a lot of excited noises (even growls to a degree) does not mean that an attack is imminent, although it also doesn't mean that your dog is just "really happy" to see their friends. But how we respond to that excitement as handlers and trainers should be consistent. We should be asking for an alternative, redirecting that energy into focusing on what we ask via commands, and waiting until the dog is not so excited to move onto any next step- especially entering a dog park. Dogs have evolved to communicate with us as part of their species survival strategy, but it feels like with more anthropomorphizing, we have lost the ability to really pick up on their cues. Each dog that I have met has shown me slightly different combinations to communicate anxiety, feeling unsure, excitement, interest, etc. It takes time with a dog to watch what happens when I introduce stimulus that is unexpected, and find any patterns that present throughout different distractions. Once I have a decent read on a dog, I can better see if their behavior starts to change. For example, right now I'm working with a gorgeous brindle pup, whose name is Stiles. Stiles is a dog who is coping with some fairly deep anxiety, which has recently started developing into near fear-aggressive reactivity. Loud, sharp barking, growling, and teeth snapping when he is stressed has given his family really strong concerns. So I'm working with him to build up his confidence, and defer to his handlers when faced with something new or potentially scary, instead of escalating his behavior. Stiles has a really sweet smile- but it becomes really "stretched" at the corners of his mouth when he is nervous. A quick glance and someone may think that he was either flashing his teeth, or just super happy. But what's actually happening is he is clearly telling me, before he starts barking, that something is upsetting him. He also tenses his back and pushes his ears high and forward. Now that I know this, as a trainer I can take him just to that line, and then reduce the stimulus and offer counter conditioning so that we can increase his tolerance positively, and at a safe speed. But it is only because I observed Stiles and have practiced learning to read dog language that I will be able to help him with problematic behaviors. Rio doesn't display this same anxiety sign, rather she hunches low, or bounces up and down like Tigger when she is nervous. Badger pants and licks his lips, Swanson whines and hides. Your dog absolutely has cues for when they are bored, when they are hungry, sick, stressed, cuddly, relaxed etc. The best thing to do when learning to read your dog is to think about whether their needs have been met, and correspond it to the behavior you are observing. So for an easy example, every night at about five pm, our dogs know that dinner is coming. They may get up, walk over to the food and water dish, stare at me, stand near the door for potty break (always before dinner), or some combination there of. They know that food is coming, and they are reminding me of the time. Swanson, if he hasn't had enough activity for the day, will come and stare directly at me, wagging at a very slow speed, and stomp his front two feet until I get the leash or redirect his behavior elsewhere by asking for a lay down or sending him to his crate. I try to project what I think the dog is communicating by remembering that dogs love patterns- so if an action corresponds to a daily routine- they may be linked. It's not enough to just notice those patterns though- we then have to figure out what to do if the escalation from the warning sign is a problematic behavior (like leash reactivity). Often a dog may also develop a behavior that's serving as an inappropriate coping skill for boredom or stress. Dogs that obsessively lick, pace, circle, etc- are all usually missing enough mental and physical stimulation throughout their day, and find that this behavior either gives them something to do or causes a human to interact with them (good or bad). Occasionally behavior patterns can cue a family into a health concern as well. Our lab mix guards food much more actively when he is sore in his hip. One of the best things one can do as a handler or owner of a pup is to read and study the most current information about body language, and then see what you can look at in your own pups and use it as a jumping off point for correcting behaviors. Aside from practice, one of the most important aspects of dog training is prevention! If I can head off a behavior before it hits peak severity- then I can reward the dog sooner for an alternative. A good jumping off point to learn more about canine body language is to check out this webinar from the ASPCA and this post from Barkpost! Today I was working with a family who live in a development with fairly strict HOA regulations. As part of those regulations, certain breeds of dogs are not permitted on the property. German Shepherds, pit bulls, shar-peis and a few other breeds (I didn't see the complete list) are not allowed to be kept in any of the homes within this community. Breed bans have largely been proved to be both ineffective and inhumane. They make absolutely no sense, and aren't based on factual research of dog aggression. But I'm not writing about that today.